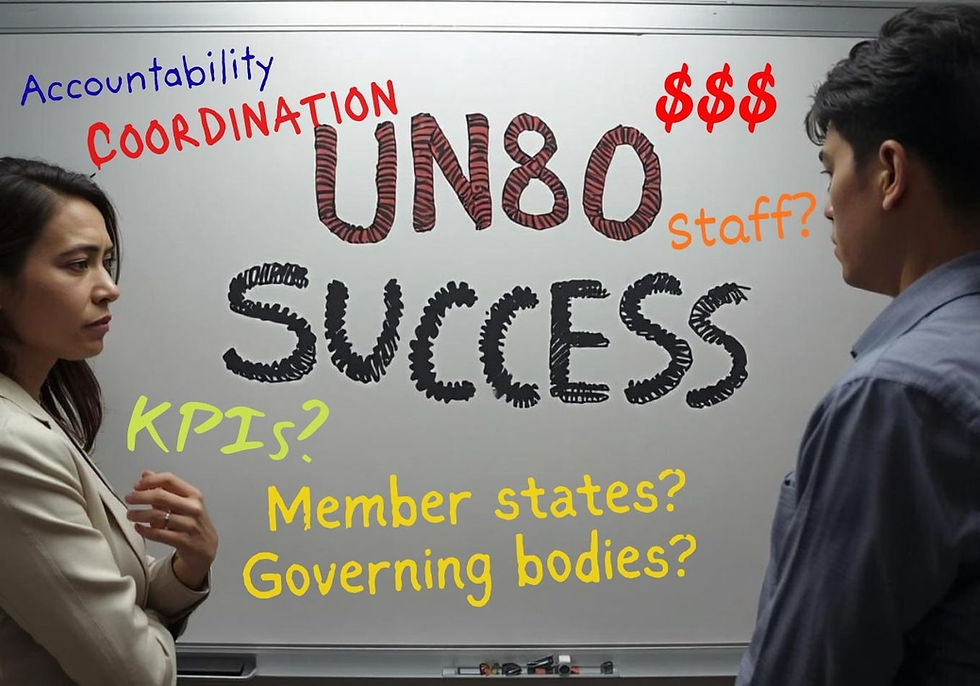

Mending Eroded Trust in the UN: A 'How to' Guide for Staff & Delegates

- Katja Hemmerich

- Aug 31, 2024

- 9 min read

Updated: Oct 14, 2024

1 Sept. 2024 (Updated on 23 Sept. 2024)

By Katja Hemmerich

New York and the world have been been gathering for the start of the UN General Assembly as well as the Summit of the Future on 22 and 23 September. The Summit of the Future intended to forge a new consensus on global cooperation and the UN. From the Secretary-General’s perspective, and that of the member states, the Summit represented a key ‘moment to mend eroded trust’ (Summit of the Future website). In the Summit’s outcome document, member states have specified that the first thing needed to improve global governance and reinvigorate the multilateral system is a United Nations that is:

“Effective and capable of delivering on our promises, with strengthened accountability, transparency and implementation mechanisms to ensure that our commitments are met and to rebuild trust in global institutions” - Pact for the Future, Action 38(a)

But how does one gauge trust in an international organization - much less rebuild it? Our spotlight this month uses new research to explore these questions.

Evaluating Trust in The United Nations

Many readers and pundits will naturally consider the extent to which the UN is invited to participate in, or lead, certain multilateral processes as a measure of trust. The limited engagement of the UN in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, for instance, is likely due to a lack of trust by some of the parties. But other political factors might also be at play, including the fact that the UN has disagreed with those member states on policy issues, or tried to hold them accountable for international standards. Trust is, therefore, a fuzzy concept to assess and not always achievable.

Many researchers take a more structural approach to the question of trust, focusing on the delegation of authority to an international organization by its member states. By virtue of the fact that member states give up their own individual authority for unilateral action when they set up or mandate international organizations, they must trust that organization to fulfill that responsibility for collective action, and trust other member states to follow its rules and procedures. Ironically, most of these same researchers focus their work on figuring out how actors try to game the system.

Most assume that the leadership and staff of international organizations are intent on gaming the system to gain more authority, resources, power, job security and/or prestige. They regularly manipulate internal information to further those aims. Member states, in turn, need to set up control mechanisms, like governing bodies, audit or evaluation mechanisms, or insist on having their staff lead those organizations, in order to keep ‘untrustworthy’ international bureaucrats from gaming the system too much. It is not hard to see how these perspectives and assumptions are reflected in some of the language around the Summit for the Future.

The problem, both for researchers and practitioners, is that this view of international organizations assumes that a lack of trust is inherent in the relationship between member states and the staff of an international organization. Trust can never really be rebuilt or ‘mended’. But is this really the case?

Fundamental to this interpretation are two assumptions. First, that the leadership and staff of international organizations are inherently self-interested and therefore are not always motivated by the collective goals of the organization and its member states. Second, it also assumes that staff in international organizations systematically try to hide or manipulate information. Most readers can probably think of examples when they have seen these behaviours at the UN, but does it really describe staff motivations and actions systematically?

It does not, according to Dr. Jörn Ege, who recently reviewed 39 studies of bureaucratic behaviors in international organizations from 2015 to 2018. Self-interested behaviors were clearly evident in almost a quarter of those studies. But in more than half the cases, staff and leadership were motivated by, and pursued, the goals of their organization, its member states and the people it served rather than self-interested goals related to resources, power or personal prestige (J. Ege, ‘What International Bureaucrats (Really) Want’, 2020).

Another researcher, Dr. Vytautas Jankauskas goes a step further to assess how different goal orientation between staff and member states and varying information flows affect trust relationships through detailed UN case studies. He argues that these dynamics are best assessed by studying the political-administrative interactions in governing bodies, which eliminates 'noise' from other extraneous factors that can influence relationships in substantive policy arenas. More importantly, these political-administrative interactions are where goals and priorities are clarified, vast amounts of information are shared and control mechanisms are enacted, allowing the aforementioned behavioral assumptions to be tested.

Dr. Jankauskas’s case studies clearly illustrate that there are different levels of trust across different UN entities and there are two distinct types of relationships between member states and staff of UN organizations. As assumed by researchers, there are UN organizations in which staff and member states do not seem to be working towards the same overarching objectives, leadership appears to be motivated by self-interest at least some of the time, and where information flows are problematic and often perceived as manipulated by member states. As expected these relationships, referred to as 'agency' relationships, are plagued by mistrust.

But there is also clearly evidence of another type of relationship in the UN, which Dr. Jankauskas calls a ‘stewardship’ relationship. In this case, the leadership acts as pro-organizational stewards focused on the best interest of the organization and its member states. There may still be disagreements over certain goals and objectives but these are resolved because the leadership readily shares information and engages actively and informally with all member states to resolve disagreements. The relationship is characterized by trust, and as a result member states exercise a softer approach to their oversight and control, relying on audit and similar mechanisms without necessarily subjecting proposals and documents to their own additional scrutiny.

The existence of stewardship relationships means that trust can and does exist, and therefore can be built or mended. So how does this work?

What builds or undermines trust?

“A steward-like administration would balance the competing preferences and find solutions in the best interest of the membership. A self-serving agent-like administration would rather ally with selected states to strengthen its own agenda.” - V. Jankauskas, 'Delegation and stewardship in international organizations', 2022

Dr. Jankauskas comparative case study of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP), which includes 39 interviews with member state delegates and FAO leadership between 2018 and 2020, provides interesting insights into the behaviors that facilitate or undermine trust. Because FAO and WFP’s governing bodies generally comprise the same member state delegates, and the organizations work on similar issues with similar structures and decision-making processes, comparing them allows insight into when and how behaviors impact relationships. Despite their structural similarities, FAO and WFP do, in fact, demonstrate very different relationships with their member states with significantly different levels of trust - very much in line with the agency and stewardship relationships that Dr. Jankauskas outlines.

Interviews with member states and leadership in FAO clearly demonstrated an agency relationship. Interlocutors in both groups highlighted clashes over the priorities of the organization, with member states perceiving the leadership to be opportunistic or unwilling to address ‘real’ issues in the eyes of member states. Delegates interviewed also consistently highlighted problems in getting the information they wanted about what is happening in FAO, with some indicating they felt the information they did receive was regularly manipulated to support the position taken by leadership. Some felt that when documents were received late and in English only it was another manipulation tactic intended to hide information from member states.

The FAO management in turn indicated that they struggled to understand what member states wanted and felt that member states constantly questioned and challenged every management position, regularly seeking out and using information from other sources to question what the management presented. As a result, governing body sessions and formal interactions with member states were very intense and inefficient:

"the degree of redundancy, duplication, and triplication of discussions is a nightmare.” - cited in V. Jankauskas, 'Delegation and stewardship in international organizations', 2022

WFP presented a very different picture, aligned with the stewardship type of relationship. Member states felt strongly that the management actively worked to accommodate the wishes of member states and was very responsive to requests from the Executive Board. The intensity of information exchange between member states and the WFP leadership is notable, through formal meetings, informal briefings and consultations, and regular meetings of regional groupings of member states and the leadership. Informal dialogues and conversations are repeatedly highlighted as an important means of constructive information-sharing, with delegates feeling that they could pick up the phone and reach out directly to clarify issues with the leadership whenever necessary. (Readers of our UN Governance News updates will probably have noted how much more often WFP schedules discussions with member states, with documents made public well in advance).

Informal exchanges do not feature at all in the FAO case study. Rather, the FAO management felt that member states did little to ask for clarification informally when they had concerns, while member states felt that the leadership tended to avoid informal dialogue to resolve concerns. One Ambassador indicated that there had been a time when the FAO leadership expressly forbade staff from informal individual meetings with Permanent Missions.

It is perhaps therefore not surprising that member states have a very different impression of the leadership in both organizations. In WFP

“The Board members might be ‘very critical and straightforward’, yet, as one ambassador highlighted, ‘even if there are these kind of conflicts, we all know that we are all working for the same purpose.’” - V. Jankauskas, 'Delegation and stewardship in international organizations', 2022

Alternatively in FAO, member states did not feel that they were all working towards the same purpose:

“it is ‘very difficult’ for them ‘to see what is happening [in the administration]’ and for what purposes: ‘is it for the future of the career of their [management’s] number one [Director-General]?’” - cited in V. Jankauskas, 'Delegation and stewardship in international organizations', 2022

Examples provided by delegates included a recent management reform and restructuring that the leadership started to implement without waiting for the endorsement of member states, when it was clear that a number of member states had strong views on the initiative.

The lack of trust is also highlighted in relation to how member states feel they are treated by the FAO leadership, with one interviewee indicating:

"FAO leadership is trying to instrumentalize the regional polarization [among membership] for the advancement of its own political purposes." - cited in V. Jankauskas, 'Delegation and stewardship in international organizations', 2022

This is vastly different than perceptions of WFP leadership, where many delegates acknowledged that they were aware that WFP leadership paid more attention to donor countries bilaterally. Yet they also stressed that all members of the Executive Board were treated with equal attention and respect, irrespective of whether they provided funding to WFP.

Techniques to foster trust

The case studies therefore start to outline the types of behaviors that UN staff and particularly its leadership can and should demonstrate if they want to rebuild trust across all parts of the UN family:

Prioritization of agreed goals and objectives to guide the way forward, in particular in reform efforts.

Regular and consistent informal engagements with member states to facilitate open information-sharing and to address member state concerns;

Comprehensive sharing of information and data on an issue by avoiding exclusion or manipulation of information that does not support what leadership is proposing;

Timely provision of written information in accordance with the organization’s rules and procedures on language, format etc.; and,

An ability to reconcile and resolve competing goals and aims into mutually agreed solutions for the way forward.

Member state delegates also have a role in developing more constructive and trusting relationships. Exercising oversight and a certain level of control over international organizations is a legitimate function for them. But how they do that very much characterizes the type of relationship that they have with that organization.

Intense scrutiny and questioning of every proposal and document does not lead to improvements in the relationship (or performance) and can incentivize withholding or manipulation of information by leadership of the UN. Requesting or organizing informal briefings, consultations or discussions with staff and leadership are better ways of gaining information and resolving concerns. This can also be done with other stakeholders such as think tanks, implementing partners and/or civil society who can share their information and data on a particular issue and facilitate validation (or correction) of information provided by the leadership of an organization or perceptions of member states. One example of this approach is WFP’s Evaluation Roundtable, in which independent evaluations with all stakeholders, including representatives of host countries or different ministries, implementing partners and NGOs, as well as member state delegates and WFP staff.

The takeaway is there is not universal mistrust of all parts of the UN - and trust can be mended where it has been eroded. Doing so will require UN leadership, staff and delegates all to intentionally change their behaviors and how they interact with each other.