From Norms to Delivery: The UN Secretariat’s Unspoken Transformation

- Thibault Camelli

- Dec 14, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 17, 2025

14 December 2025

By Thibault Camelli

The United Nations (UN) is undergoing a structural shift: the Organization’s Secretariat is gradually transforming from a normative body into an operational institution. While delivery has long existed within the UN system through Funds and Programmes, it was deliberately structured outside the Charter’s normative core to preserve sovereignty and limit the Secretariat’s executive authority. Over time, however, delivery expectations have crept into Secretariat governance and mandate evaluation.

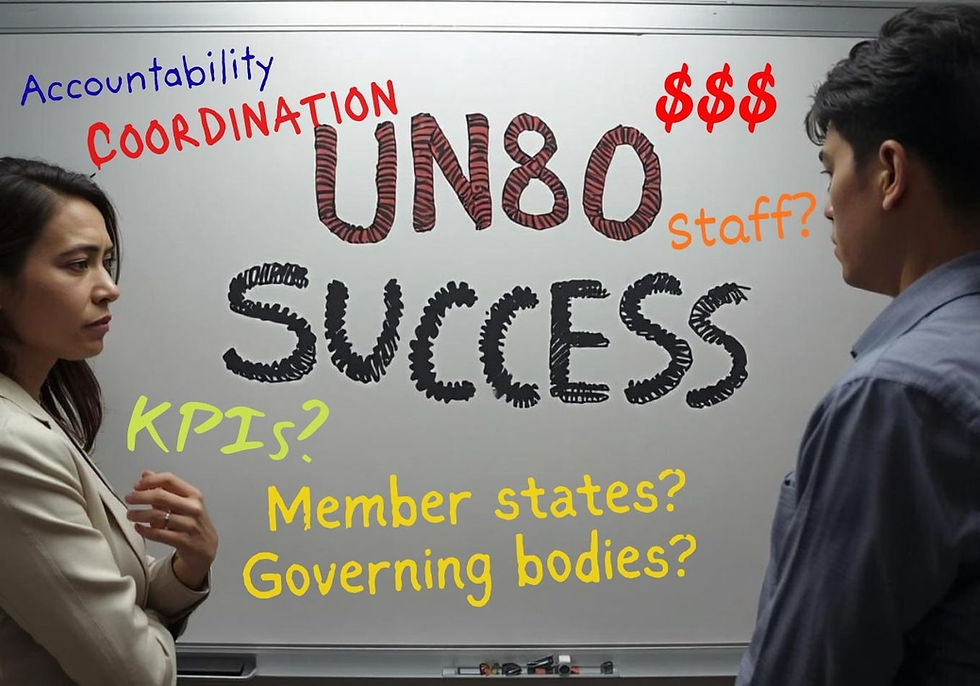

This shift reflects the structural rise of voluntary and earmarked financing, which has privileged measurable outputs over declaratory norm-setting. The General Assembly does not explicitly endorse this transformation, yet it was formalized as the operational logic of all successive reforms since Kofi Annan’s “Track One” management reform in 1997, to the UN80 Initiative’s slogan: “United to Deliver”.

“Reform is not an end in itself. The purpose of reform is simple and clear: to best position the United Nations to deliver on humanity’s boldest agenda: the Sustainable Development Goals” — UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

Crucially, this shift does not replace the UN Secretariat’s normative mandate: convening, standard-setting, and political coordination remain foundational, but they are no longer considered sufficient. Beyond its ability to shape norms, the Secretariat is increasingly judged on its capacity to deliver on the outcomes those norms imply. Understanding this new expectation is essential for interpreting what UN80 signals about the future of multilateralism.

Finding coherent solutions to reconcile the tensions this new expectation brings will be key to the success of the Informal Ad Hoc Working Group on Mandate Implementation and the broader UN80 reforms.

The Secretariat Was Designed to Set Norms, Not Execute Them

The Secretariat’s institutional core was built around standard-setting, deliberation, and the progressive development of international norms. The UN Charter’s framers deliberately avoided designing an operational executive: the Secretariat was intended to facilitate political coordination, synthesize inputs, and support collective decision-making. Delivery functions were delegated to Funds and Programmes (e.g., the UN Children's Fund, UNICEF, or the UN Development Programme, UNDP).

This separation between normative and operational functions was intentional: it preserved sovereignty, limited the Secretariat’s executive authority, and ensured that implementation rested outside the normative core. Peacekeeping—and later humanitarian action—evolved through pragmatic exception rather than constitutional design. Those exceptions were tolerated precisely because they were limited; norm-setting remained the core, delivery the outlier. For decades, the arrangement was stable: the Secretariat set norms; others delivered on them.

From Norm to Delivery: Three Decades of Earmarked Funding Triggered a Shift that Successive Reforms Institutionalized

The past three decades blurred this clarity first through delivery expectations shaped by voluntary financing, and second, through their gradual codification in successive reforms.

Voluntary and extra-budgetary funding streams progressively conditioned financing on demonstrable outputs and program delivery. This logic extended delivery into the Secretariat, and financing operated as a structural driver: evidence of implementation became a prerequisite for continued funding, intensifying delivery expectations without any corresponding adjustment of authorities, budget rules, or Secretariat decision latitude.

Successive reforms then codified this shift incrementally. Kofi Annan initiated this movement with management reform (1997) and “Delivering as One” (2005). Ban Ki-moon’s field support initiative continued it and further operationalized peacekeeping. In 2017, António Guterres launched the restructuring of peace and security, the repositioning of the development system and management reform (with delegation of authority, performance compacts, and enterprise risk systems). Collectively, these reforms ultimately resulted in a structural shift in member states’ perception of the Secretariat’s normative role: norms now carry delivery expectations.

Oversight bodies reinforced the same logic. Evaluation and audit shifted from compliance towards delivery measurement. Budget instruments were established to emphasize results-based budgeting. Executive Offices introduced dashboards and progress tracking: the tools of operational management became everyday governance instruments.

UN80 accelerates this trajectory. What earlier reforms absorbed incrementally, UN80 frames explicitly: delivery is no longer a by-product of financing incentives but a design premise of mandate governance. Workstreams on mandate review, resource use, and structural realignment assume that mandates require costing, sequencing, feasibility analysis, and performance feedback. These are delivery concepts, not diplomatic ones.

Member states now judge the Secretariat by results, but have not adjusted financing or the structures that enable results. Delegation of authority remains bounded by oversight, staffing statutes, and political caution. Even more acutely clear in the current liquidity crisis, the UN financing system, designed for deliberation, proves strained and inadequate to support implementation. This is the core mismatch.

Peacekeeping and humanitarian operations were originally designed as narrow, exceptional domains capable of reallocation, surge, and operational responsiveness. They are now treated as the de facto benchmark for how the wider UN should behave, despite the rest of the system lacking the legal authorities, financial elasticity, or mandate coherence.

In practice, the delivery logic evolved as an exception to the normative core, which was never structurally redesigned to absorb it. The operational tail has now grown from an exception to the general rule, but the system has remained structured around normative expectations without an accompanying institutional redesign. As a result, expectations of what it means for the UN to hold a normative mandate have gradually changed: the UN is still expected to define standards, but is now also asked to execute them, monitor them, and demonstrate their impact. This tension is most visible in the field: Country teams are increasingly asked to show “unity of approach” and measurable impact, while many of the mandates that drive their workload are still negotiated in New York. This disconnect was raised in various ways by many briefers of the Informal Ad Hoc Working Group, including, most directly, by Ameerah Haq: mandate design remains diplomatic, while its evaluation has become operational.

The result is a growing disconnect between how mandates are drafted and how they must be delivered. This shift now requires member states to treat mandate language as more than declaratory instruction but as operational commitments, with implications for costing, staffing, and sequencing.

Delivery Expectations Have Entered Mandate Governance at the UN Secretariat

The UN80 mandate review marks the moment where delivery becomes an evaluation criterion. A normative institution adopts mandates based on consensus; a delivery institution asks if those mandates are implementable, sequenced, resourced, and reviewable. This lifecycle—creation, implementation, review—does not negate norms but subjects them to feasibility tests. Mandate consolidation, sequencing, and feedback loops are the operational necessities once norms become performance obligations.

This mismatch becomes operationally visible in the Fifth Committee, where delivery obligations confront financing limits and where mandates acquire real implementation consequences. The Fifth Committee reveals the logic the system is drifting towards. Although one of the main committees of the General Assembly, the Fifth Committee is often mischaracterized as technical, yet it is where mandates take on operational consequence: where costs are assigned, staffing is accepted or rejected, delivery risks are acknowledged, and oversight findings are absorbed.

Its culture aligns with the broader evidence on the performance of international organizations (IOs). As Ranjit Lall notes, IO performance improves when accountability relationships include multiple stakeholders and when information flows are sufficiently rich to discipline decision-making.

“MSA [Multi-stakeholder accountability] reforms have ushered in a new era of transparency, inclusiveness, and responsiveness in global governance.” - R. Lall, "Making Global Governance Accountable: Civil Society, States, and the Politics of Reform", 2023

In practical terms, this means that delegations are exposed not only to Secretariat proposals but also to findings from oversight bodies, evaluations, and—increasingly—feedback from implementing partners and affected communities. Accountability reflects a broader range of stakeholders, not just formal principals.

This description fits the Fifth Committee’s practice: multi-stakeholder negotiation anchored in real costing, oversight inputs, and documented delivery risks. Five practices illustrate the ethos:

1. Constructive engagement: problem-solving through early surfacing of constraints.

2. Collegial inclusion: participation as legitimacy, not symbolism.

3. Concreteness: debates grounded in costs, staffing, timelines, and risks.

4. Corroboration: evidence and oversight used to refine, not merely review.

5. Consensus: durability of outcomes over speed of adoption.

This is not a template to replicate system-wide; Fifth Committee procedures are slow and negotiated. But its logic is instructive: when norms acquire delivery obligations, procedural discipline becomes a political necessity.

UN80 Confirms the Shift to Delivery-Based Mandate Design

Workstream 1 reframes efficiency from cost containment to alignment between ambition and delivery capacity.

Workstream 2 makes the dual mandate explicit: feasibility becomes a condition of political intent.

Workstream 3 addresses structure: authorities and accountabilities must match operational expectations.

Across all three, the underlying transformation is consistent: a normative body now evaluated through operational metrics must reconcile roles before designing tools. UN80 surfaces a choice that has long been implicit. The point is not to choose between norm-setting and delivery, but to recognize that delivery has been added to norm-setting without redesigning the system to handle both. Convening is still necessary; it is simply no longer sufficient.

Overall, the UN80 Initiative reveals a tension, but at this point, it has not found a way to resolve it: the Secretariat can no longer sustain a normative architecture evaluated as a delivery agency. This is the new frontier for multilateral reform, and if the UN80 Initiative can address it, the UN can emerge as a stronger organization.

Thibault Camelli is a former Fifth Committee delegate currently working at the Multilateral Reform Program at New York University’s Center on International Cooperation (CIC).