Adaptability: The UN's Tool for Navigating Hard Power Politics

- Jan 11

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 12

11 January 2026

By Katja Hemmerich

On 5 January 2026, White House Deputy Chief of Staff, Stephen Miller, confirmed what many already suspected - that the United States no longer believes in the efficacy of a rules-based international order, but perceives the ‘real world’ as governed by strength, force and power. While the Trump administration has been the most explicit in embracing this shift, it can also be seen in Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, and the US policy (of the last three administrations) to prevent the appointment of arbitration judges to the World Trade Organization (WTO), late or non-payment of assessed funds by the largest contributors, and the growing use of earmarked voluntary funding by wealthy member states to push their priorities in the UN without negotiating a consensus across the membership.

While these symptoms may be specific to our current time, the predominance of hard power politics is nothing new. For most of its existence, the UN has been forced to navigate hard power politics and the refusal to adhere to international norms and laws by major powers. And yet, the UN has shown a remarkable resilience.

We start 2026, therefore, with a look back at how the UN has navigated such geopolitical dynamics in the past. What the research highlights is that the UN - contrary to public perception - has a surprising ability to adapt. Our spotlight traces some of those adaptations and outlines the tactics and skills that member states and UN staff have used to facilitate these adaptations and navigate hard power politics.

The UN Charter and the Balance of Power

“States are not equal but vary in terms of their material power. Cooperation in international organizations (IOs) does not change this fact, as material power tends to be translated into institutional outcomes.” - B. Dassler et al. “Insuring the Weak: The Institutional Power Equilibrium in International Organizations”, 2024

The UN, like all international organizations, has always recognized the reality that power in the international system is unevenly dispersed. The founders of the UN acknowledged this and built power disparities into the structure of the organization, making the most powerful member states after the Second World War permanent members of the Security Council, which in turn was granted with powers of ‘action’. The Security Council wields the UN’s limited enforcement power through Articles 6 and 7 of the UN Charter when it deems there has been a breach of international peace.

The General Assembly, in turn creates a more level playing field between member states, giving each country an equal vote. This balance in voting power was, however, intended to provide a collective legitimacy to agreements that in the end are only recommendations and not binding resolutions, like those of the Security Council. As the chairperson of the relevant committee at San Francisco stated in 1945:

“The Assembly, as the supreme representative body of the world, is to establish the principles on which world peace and ideal of solidarity must rest; and, on the other hand, the Security Council is to act in accordance with those principles and with the speed necessary to prevent any attempted breach of international peace and security. In other words, the former is a creative body and the latter an organ of action.” - cited in G.R. Lande, “The Effect of the Resolutions of the United Nations General Assembly”, 1966.

Yet, reality played out very differently. The only time that the UN functioned as intended was during the post-Cold War era. The most obvious example being the proliferation of peace operations, in particular from 1999-2015 authorized by the Security Council under Articles 6 and 7 with collective engagement and legitimacy supported by Fourth Committee of the General Assembly. For the remaining 64 years of its existence, the UN has had to navigate geopolitical conditions marked by tension and competition between major powers, who have demonstrated their willingness and ability to ignore or circumvent international norms and rules, when it suited them.

UN Adaptability as a Response to Power Politics

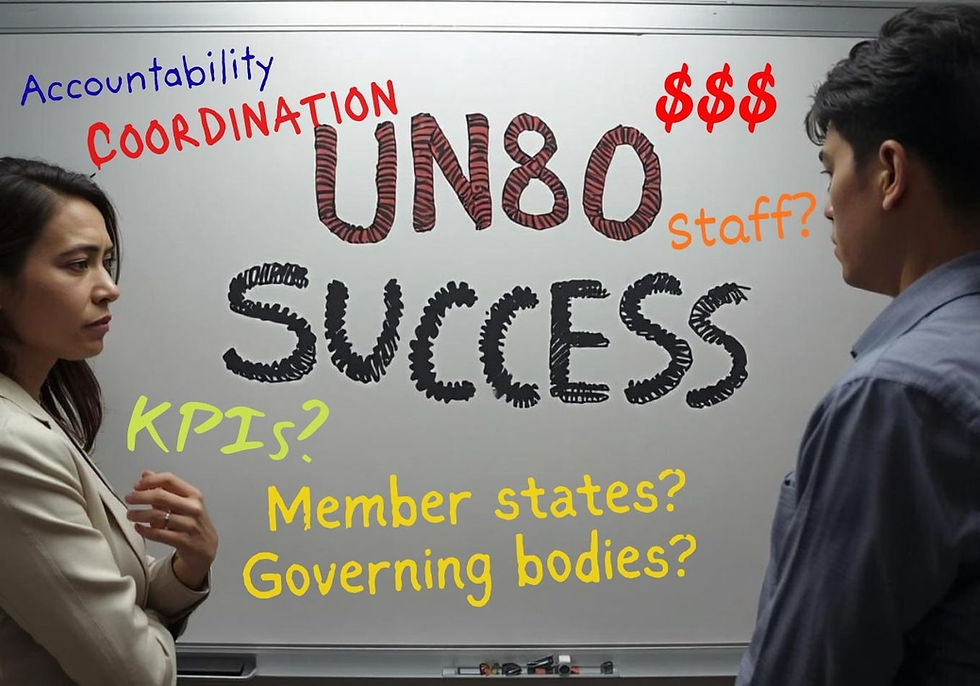

As outlined by our recent guest contributor, Thibault Camelli, one of the tensions exposed in the UN80 discussions is that the members of the General Assembly have an expectation of action and delivery when they agree mandates. The idea that the General Assembly is a purely creative or normative organ and the Security Council is the only organ of action no longer holds. This adaptation has not come about by accident, but is in fact an evolutionary response to the hard power politics that plagued the UN right from the start.

By the 1960s, scholars were already highlighted that Cold War conflicts prevented the UN from functioning as intended. Hard power politics typically prevented the Security Council from finding agreement on ‘action’, creating a window of opportunity for the General Assembly to become an “organ of action”. Most readers will be familiar with the Uniting for Peace resolution, initiated by the US, during the Korean conflict in the 1950s, which outlined when the General Assembly could act on peace and security in the face Security Council non-action.

But there were also many instances of less powerful states engaging to adapt the General Assembly’s role in the face of hard power politics, for instance by creating the Eighteen-Nation Disarmament Committee, which paved the road for eventual agreement of the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, despite a lack of interest by the US and USSR in curbing nuclear capabilities. Similarly, when colonial powers were reluctant to voluntarily put their colonies under trusteeship in accordance with Article 77 of the Charter, a majority of smaller and often newer states created the Committee on Information from Non-Self-Governing Territories and Committee on South West Africa to enable the decolonization process.

What these examples highlight is that throughout the UN’s history, its bodies have had agency, and been able to use it for adaptation of the multilateralism, even in the face of great power resistance. Ironically, with our 21st century focus on effective management, many of these examples would be called out as inefficient and duplicative. This is precisely why effective management of the UN needs to understand that it is an organization subject to hard power politics between its member states, rather than a corporate organization that happens to have member states on its board.

Skills and Tactics for Adaptation

The UN’s ability to adapt has been underpinned by an ability to increase the autonomy of certain bodies (meaning their ability to act) while respecting the formal authorities and roles set out in the Charter. While there is no set formula for how to make this happen, research has highlighted several elements that have contributed to adaptation and increased autonomy of UN entities.

One of the most important is that successful adaptations are based on legislative procedures that are considered by the majority of member states (and the global public) to be fair and transparent (see for instance L. Dellmuth et al., Institutional sources of legitimacy for international organisations: Beyond procedure versus performance", 2019). The Security Council approval of UN intervention in the Korean War, which was known to be opposed by the Soviet Union, but that was obtained solely because the USSR was boycotting the Council did not lead to lasting adaptation in the UN - and also led to the first breakdown of consensus in Fifth Committee budget decisions. But the overwhelming majority of votes in the General Assembly in favor of the Uniting for Peace resolution did. This precedent and approach was still useful more than 60 years later, when the General Assembly approved the creation of another adaptive innovation in the face of Security Council inaction, the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism for Syria (IIIM).

Adaptation and innovations are also most often undertaken by member states and UN staff working collaboratively. The sponsors of the resolution establishing the IIIM, Liechtenstein and Qatar, worked closely with staff from the Office of the High Commissioner who provided technical advice on how the Mechanism could be set up. Similar collaboration between Dag Hammarskjold and the then Foreign Minister of Canada, Lester Pearson, established UNEF I and the precursor to peacekeeping operations we know today - another adaptation never explicitly envisaged in the Charter. But this collaboration was also underpinned by procedural legitimacy. Hammarskjold had long advocated for greater autonomy of the Office of the Secretary-General in peace and security even when the Council was engaged. Although this independence was not always welcome by major powers, it was accepted and became known as the Peking Formula. In the Suez Crisis and his other engagements, he consistently adhered to the principle that:

“the Secretary-General had a right and obligation to involve himself and could take a ‘neutral stance’ independent of the Council’s position”. - T. Myint-U & A. Scott, “The UN Secretariat - A Brief History (1945-2006)", 2007.

This impartiality, which adhered to the spirit of the Charter and authority set out in Article 99, is an important competency not just for Secretary-Generals but all UN staff who support adaptation. This impartiality combined with strong technical and substantive expertise has been evident in Ralphe Bunche’s support for the development of peacekeeping or OHCHR’s support for the creation of the IIM. It is also often an important resource to help smaller delegations with less capacity than the most powerful member states to engage meaningfully on an issue - a point which was highlighted in the interim report of the Informal Adhoc Working Group on UN80 in December 2025.

A 1962 appraisal of the UN’s work on colonialism provides interesting insights into how the impartiality and expertise of UN staff can help further the ideals of the Charter and mitigate hard power politics, especially when one considers that at the time, 80% of UN staff were from North America or Western Europe:

“The Secretariat’s expert knowledge concerning some of the more technical issues in the colonial field has caused many delegates to rely heavily on it as a source of advice. They have also been willing to allow it considerable discretion in handling day-to-day colonial issues… although the Secretariat’s knowledge has been available to all, it has been more useful to these [smaller] delegations, for their national staffs could hardly match those of the colonial powers. More importantly the sympathies of the UN Secretariat appear generally to have tended in this direction.” - H.K. Jacobsen, “The UN and Colonialism: A Tentative Appraisal”, 1962

UN Adaptability Takeaways

While the return to hard power politics in the multilateral system has been unnerving, it is not unprecedented, and is in fact baked into the design of the UN. The unprecedented levels of collaboration and consensus amongst member states that many of us working with an for the UN have experienced in recent decades, is sadly the exception rather than the rule. But that also means that history can demonstrate how the UN needs to navigate this new era. Our brief overview highlights a few important takeaways:

Adherence to the values and tenets of the UN Charter matters - even when stronger powers choose to ignore it;

A strong understanding of legislative authorities and processes, and where there is room for agency and autonomy, is crucial for UN delegates and staff navigating hard power politics and facilitating adaptation;

Procedural fairness and legitimacy is an essential foundation for any organizational, procedural or political adaptation and innovation;

Collaboration between member states (of all sizes and strengths) and UN staff leads to innovation and adaptation;

A political as well as managerial understanding of why a duplication or inefficiency exists should inform decisions about how, when or whether to eliminate that redundancy.